While we’re tracking Garrett Mt. developments, we’re obliged to reprise our favorite local eco-real estate story exerpted from 11/04:

While we’re tracking Garrett Mt. developments, we’re obliged to reprise our favorite local eco-real estate story exerpted from 11/04: Where Dinosaurs Once Roamed

By Samantha Henry HERALD NEWS

(Original research by Bloomfield’s own Mary Shaughnessy)

WEST PATERSON -The layers of rock at the Tilcon quarry near Garret Mountain read like the history of North Jersey. The most recent layer is a pending condominium development on the site; the oldest dates back 200 million years. It contains fossilized dinosaur footprints that scientists have been quietly removing from the area for decades in an effort to save them.

Now the quarry and surrounding land at the Clifton-West Paterson border have been sold to the developer K. Hovnanian, which plans to build 810 condominium units there. Construction of the complex will soon fill in the quarry that yielded the specimens. Workers will rebury the layer of volcanic rock that provided a brief and rare snapshot of a time when dinosaurs roamed the Newark basin - a vast geological depression from the Palisades to Pennsylvania - during the early Jurassic era.

"For this time interval, it's probably the most important site in New Jersey," said William B. Gallagher, registrar of natural history for the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton. "It's one of the best sites for looking at the early phase of dinosaurs, and the beginning of the trend towards gigantivism," he said, referring to the huge meat-eating dinosaurs that appeared at the transition point between the Triassic and Jurassic eras. Fossilized dinosaur footprints can be found across North Jersey, but they are buried in a layer of earth that is often exposed only through quarrying and other deep-digging processes, Gallagher said. For the three dozen or so dinosaur footprints that Gallagher and his colleagues have found at the site over the years, he said, countless more were probably damaged or lost in the quarrying process. "A lot of 'salvage paleontology' involves getting into these places and getting what we can before it's destroyed," he said. "It's the difficulty of trying to preserve geologic history with accelerated development. Nowhere is that more evident than in New Jersey, where we're rapidly running out of room."

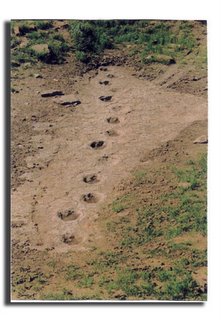

The Tilcon quarry on Garret Mountain - referred to locally by the names of its many previous owners, such as UBC, Hamilton, and Dell - has been mined for nearly a century. Chris Laskowich, a science teacher at Paterson's Eastside High School who grew up next to the Garret Mountain site in West Paterson, credits the quarries across North Jersey for exposing prehistoric layers of rock that would have otherwise remained buried. "The geology for the area got a real head start in Paterson, because of the heroic, immigrant, blue-collar workers who started these quarries which made all our highways. They started this science," Laskowich said. One of the most pristine dinosaur footprints found at the site is displayed at the state museum. Preserved in a chunk of red rock, it shows the three-toed imprint of a Eubrontes giganteus, Gallagher said.

He said dinosaur footprints provide a great deal of information about how the animal lived, and tracks found in succession can provide clues as to how fast it could move.

The specimen from Garret Mountain would have been a huge carnivorous dinosaur, probably a Dilophosaurus, which weighed more than a ton, stood on two hind legs, and had a long, powerful tail and two thin ridges of bone on its head, Gallagher said.

He described the landscape of prehistoric North Jersey as a large valley surrounded by molten lava flows at a time when all the continents were connected in a single landmass. "Africa was right next door to New Jersey. You could have walked from Newark to Morocco," Gallagher said. The particular geological makeup of North Jersey - the basalt (volcanic rock) that is found in quarries across the area - preserves fossil footprints better than it does skeletons or bones, and the two are rarely found together, Gallagher said.

Though New Jersey's physical conditions may be favorable for preserving prehistoric fossils, the state's laws are not. Paleontological discoveries, regardless of age, are not protected by law as they are in some other states. In New Jersey, only archaeological finds - those involving human bones and remains - are granted legal protection. A bill to add protection for "geologically significant sites" into the Natural Areas law was introduced in 1999 by state Sen. Leonard Lance, R-Flemington, but it has not been passed. Although Gallagher and Laskowich said they would like to see the Tilcon quarry site preserved, they said such an expensive, cumbersome undertaking would require a continued funding stream that most scientific institutions do not have. Laskowich, whose home will overlook the new Hovnanian development, said he wishes the company would at least acknowledge what was there before. "By definition, there is no destruction by developers," Laskowich said. "It's already been destroyed by the quarrying. What's sad is that there isn't one little corner, the size of just one housing unit, that will be saved to show the surface." Gallagher, who teaches a course in dinosaurs at Rutgers University, said the site would make a great educational location, where students and the public could study fossils and see the footprints. Gallagher and Laskowich referred, in separate interviews, to the impending condominium development on the site as just another layer in the strata of local history scientists will rediscover one day. "This is New Jersey," Laskowich said. "We pave over historic sites. It's like the song says: 'They paved paradise and put up a parking lot.' "

No comments:

Post a Comment